TypeScript Office - 类

TypeScript Office - 类

# 类

TypeScript 提供了对 ES2015 中引入的 class 关键词的完全支持。

与其他 JavaScript 语言功能一样,TypeScript 增加了类型注释和其他语法,允许你表达类和其他类型之间的关系。

# 类成员

这里有一个最基本的类,一个空的类:

class Point {}

这个类还不是很有用,所以我们开始添加一些成员。

# 类属性

在一个类上声明字段,创建一个公共的可写属性。

class Point {

x: number;

y: number;

}

const pt = new Point();

pt.x = 0;

pt.y = 0;

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

与其他位置一样,类型注解是可选的,但如果不指定,将是一个隐含的 any 类型。

字段也可以有初始化器;这些初始化器将在类被实例化时自动运行。

class Point {

x = 0;

y = 0;

}

const pt = new Point();

// Prints 0, 0

console.log(`${pt.x}, ${pt.y}`);

2

3

4

5

6

7

就像 const、let 和 var 一样,一个类属性的初始化器将被用来推断其类型。

const pt = new Point();

pt.x = "0"; // 报错:px.x 是 number 类型

2

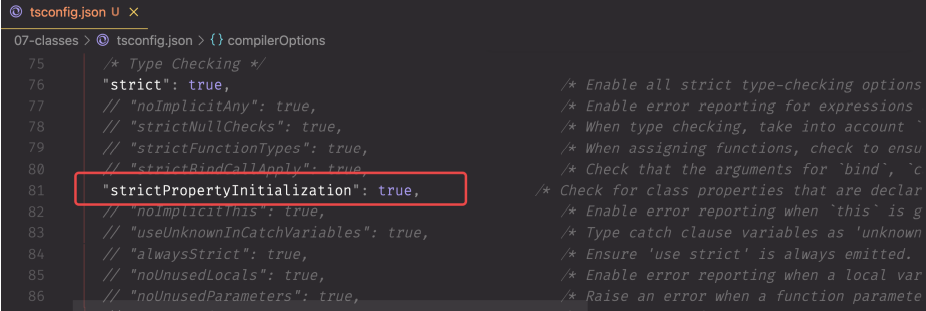

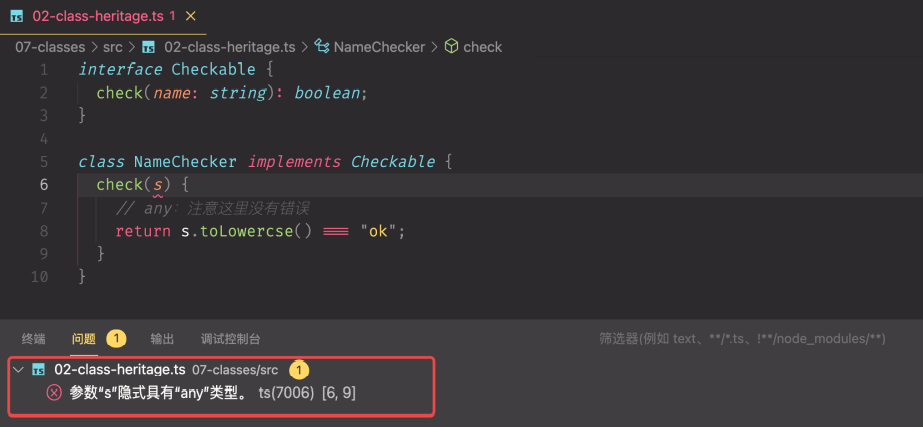

--strictPropertyInitialization

strictPropertyInitialization 设置控制是否需要在构造函数中初始化类字段。

class BadGreeter {

name: string;

}

2

3

class GoodGreeter {

name: string;

constructor() {

this.name = "hello";

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

请注意,该字段需要在构造函数本身中初始化。TypeScript 不会分析你从构造函数中调用的方法来检测初始化,因为派生类可能会覆盖这些方法而无法初始化成员。

如果你打算通过构造函数以外的方式来确定初始化一个字段(例如,也许一个外部库为你填充了你的类的一部分),你可以使用确定的赋值断言操作符 !。

class OKGreeter {

// 没有初始化,但没报错。

name!: string;

}

2

3

4

# readonly

字段的前缀可以是 readonly 修饰符。这可以防止在构造函数之外对该字段进行赋值。

class Greeter {

readonly name: string = "world";

constructor(otherName?: string) {

if (otherName !== undefined) {

this.name = otherName;

}

}

err() {

this.name = "not ok";

}

}

const g = new Greeter();

g.name = "also not ok";

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

# 构造器

类构造函数与函数非常相似。你可以添加带有类型注释的参数、默认值和重载:

class Point {

x: number;

y: number;

// 带默认值的正常签名

constructor(x = 0, y = 0) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

class Point {

// 重载

constructor(x: number, y: string);

constructor(s: string);

constructor(xs: any, y?: any) {

// ...

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

类的构造函数签名和函数签名之间只有一些区别:

- 构造函数不能有类型参数,这属于外层类的声明,我们将在后面学习

- 构造函数不能有返回类型注释,类的实例类型总是被返回的

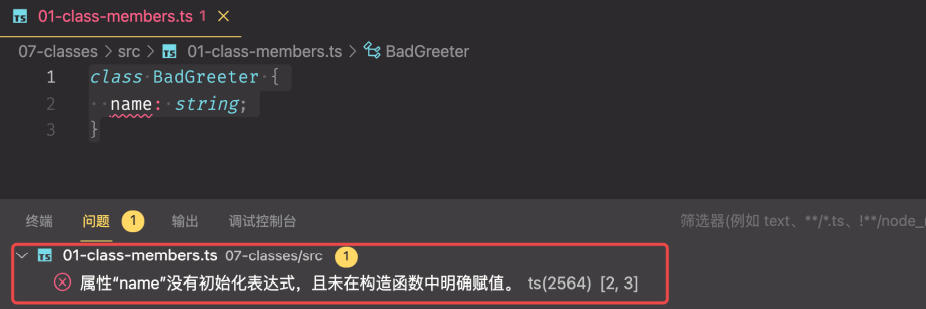

# Super 调用

就像在 JavaScript 中一样,如果你有一个基类,在使用任何 this. 成员之前,你需要在构造器主体中调用 super();。

class Base {

k = 4;

}

class Derived extends Base {

constructor() {

// 在ES5中打印一个错误的值;在ES6中抛出异常。

console.log(this.k);

super();

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

在 JavaScript 中,忘记调用 super 是一个很容易犯的错误,但 TypeScript 会在必要时告诉你。

# 方法

一个类上的函数属性被称为方法。方法可以使用与函数和构造函数相同的所有类型注释。

class Point {

x = 10;

y = 10;

scale(n: number): void {

this.x *= n;

this.y *= n;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

除了标准的类型注解,TypeScript 并没有为方法添加其他新的东西。

请注意,在一个方法体中,仍然必须通过 this 访问字段和其他方法。方法体中的非限定名称将总是指代包围范围内的东西。

let x: number = 0;

class C {

x: string = "hello";

m() {

// 这是在试图修改第1行的'x',而不是类属性。

x = "world";

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# Getters / Setters

类也可以有访问器:

class C {

_length = 0;

get length() {

return this._length;

}

set length(value) {

this._length = value;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

请注意,一个没有额外逻辑的字段支持的 get/set 对在JavaScript中很少有用。如果你不需要在 get/set 操作中添加额外的逻辑,暴露公共字段也是可以的。

TypeScript 对访问器有一些特殊的推理规则:

- 如果存在 get,但没有 set,则该属性自动是只读的

- 如果没有指定 setter 参数的类型,它将从 getter 的返回类型中推断出来

- 访问器和设置器必须有相同的成员可见性

从 TypeScript 4.3 开始,可以有不同类型的访问器用于获取和设置。

class Thing {

_size = 0;

get size(): number {

return this._size;

}

set size(value: string | number | boolean) {

let num = Number(value);

// 不允许NaN、Infinity等

if (!Number.isFinite(num)) {

this._size = 0;

return;

}

this._size = num;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

# 索引签名

类可以声明索引签名;这些签名的作用与其他对象类型的索引签名相同。

class MyClass {

[s: string]: boolean | ((s: string) => boolean);

check(s: string) {

return this[s] as boolean;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

因为索引签名类型需要同时捕获方法的类型,所以要有用地使用这些类型并不容易。一般来说,最好将索引数据存储在另一个地方,而不是在类实例本身。

# 类继承

像其他具有面向对象特性的语言一样,JavaScript 中的类可以继承自基类。

# implements 子句

你可以使用一个 implements 子句来检查一个类,是否满足了一个特定的接口。如果一个类不能正确地实现它,就会发出一个错误。

interface Pingable {

ping(): void;

}

class Sonar implements Pingable {

ping() {

console.log("ping!");

}

}

class Ball implements Pingable {

pong() {

console.log("pong!");

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

类也可以实现多个接口,例如 class C implements A, B {。

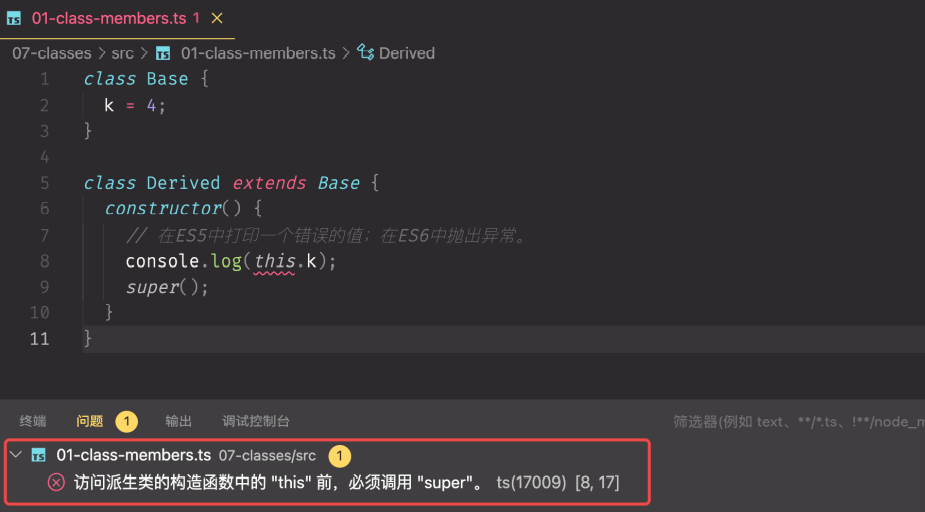

# 注意事项

重要的是要明白,implements 子句只是检查类是否可以被当作接口类型来对待。它根本不会改变类的类型或其方法。一个常见的错误来源是认为 implements 子句会改变类的类型,它不会,它不会!

interface Checkable {

check(name: string): boolean;

}

class NameChecker implements Checkable {

check(s) {

// any:注意这里没有错误

return s.toLowercse() === "ok";

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

在这个例子中,我们也许期望 s 的类型会受到 check 的 name: string 参数的影响。事实并非如此,实现子句并没有改变类主体的检查方式或其类型的推断。

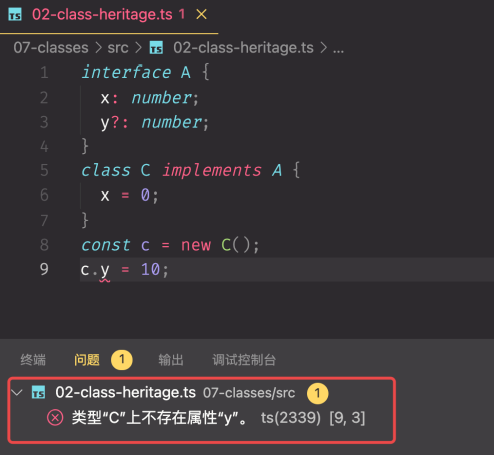

同样地,实现一个带有可选属性的接口并不能创建该属性。

interface A {

x: number;

y?: number;

}

class C implements A {

x = 0;

}

const c = new C();

c.y = 10;

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

# extends 子句

类可以从基类中扩展出来。派生类拥有其基类的所有属性和方法,也可以定义额外的成员。

class Animal {

move() {

console.log("Moving along!");

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

woof(times: number) {

for (let i = 0; i < times; i++) {

console.log("woof!");

}

}

}

const d = new Dog();

// 基类的类方法

d.move();

// 派生的类方法

d.woof(3);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# 重写方法

派生类也可以覆盖基类的一个字段或属性。你可以使用 super. 语法来访问基类方法。注意,因为 JavaScript 类是一个简单的查找对象,没有「超级字段」的概念。

TypeScript 强制要求派生类总是其基类的一个子类型。

例如,这里有一个合法的方法来覆盖一个方法。

class Base {

greet() {

console.log("Hello, world!");

}

}

class Derived extends Base {

greet(name?: string) {

if (name === undefined) {

super.greet();

} else {

console.log(`Hello, ${name.toUpperCase()}`);

}

}

}

const d = new Derived();

d.greet();

d.greet("reader");

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

派生类遵循其基类契约是很重要的。请记住,通过基类引用来引用派生类实例是非常常见的(而且总是合法的)。

// 通过基类引用对派生实例进行取别名

const b: Base = d;

// 没问题

b.greet();

2

3

4

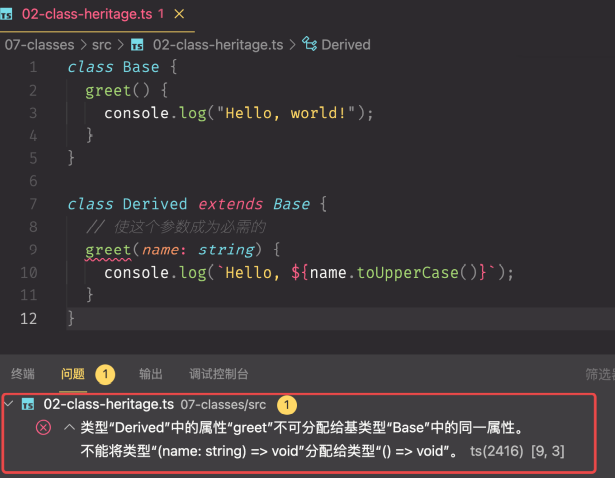

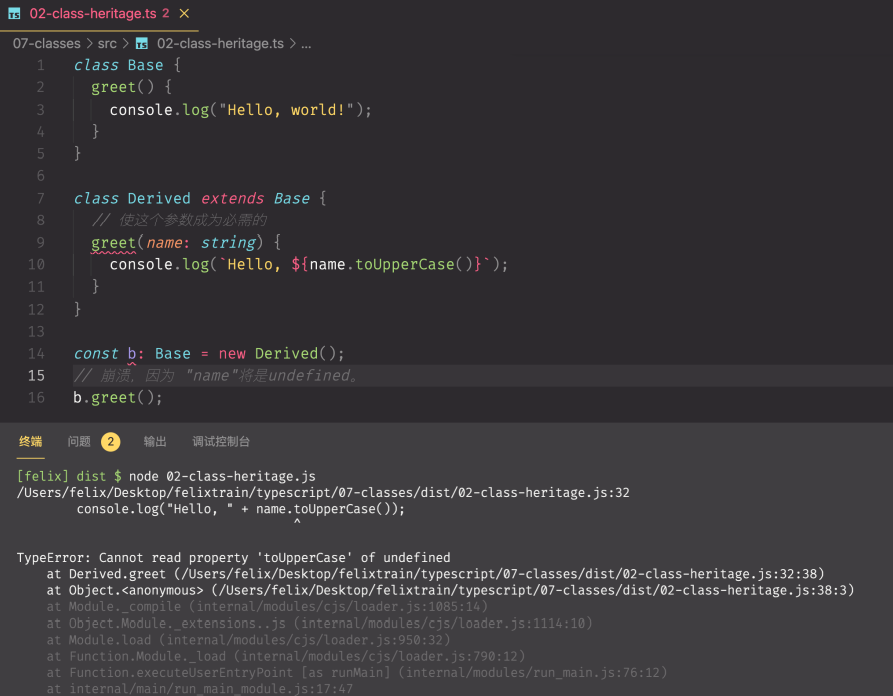

如果 Derived 没有遵守 Base 的约定怎么办?

class Base {

greet() {

console.log("Hello, world!");

}

}

class Derived extends Base {

// 使这个参数成为必需的

greet(name: string) {

console.log(`Hello, ${name.toUpperCase()}`);

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

如果我们不顾错误编译这段代码,这个样本就会崩溃:

const b: Base = new Derived();

// 崩溃,因为 "名称 "将是 undefined。

b.greet();

2

3

# 初始化顺序

在某些情况下,JavaScript 类的初始化顺序可能会令人惊讶。让我们考虑一下这段代码:

class Base {

name = "base";

constructor() {

console.log("My name is " + this.name);

}

}

class Derived extends Base {

name = "derived";

}

// 打印 "base", 而不是 "derived"

const d = new Derived();

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

这里发生了什么?

按照 JavaScript 的定义,类初始化的顺序是:

- 基类的字段被初始化

- 基类构造函数运行

- 派生类的字段被初始化

- 派生类构造函数运行

这意味着基类构造函数在自己的构造函数中看到了自己的 name 值,因为派生类的字段初始化还没有运行。

# 继承内置类型

注意:如果你不打算继承 Array、Error、Map 等内置类型,或者你的编译目标明确设置为 ES6/ES2015 或以上,你可以跳过本节。

在ES2015中,返回对象的构造函数隐含地替代了 super(...) 的任何调用者的 this 的值。生成的构造函数代码有必要捕获 super(...) 的任何潜在返回值并将其替换为 this 。

因此,子类化 Error、Array 等可能不再像预期那样工作。这是由于 Error 、 Array 等的构造函数使用 ECMAScript 6 的 new.target 来调整原型链;然而,在 ECMAScript 5 中调用构造函数时,没有办法确保 new.target 的值。其他的下级编译器一般默认有同样的限制。

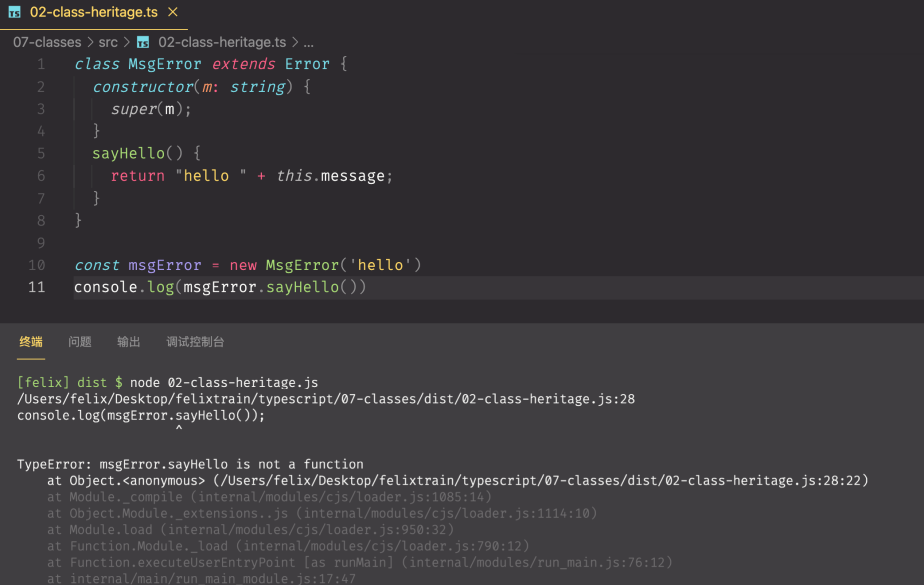

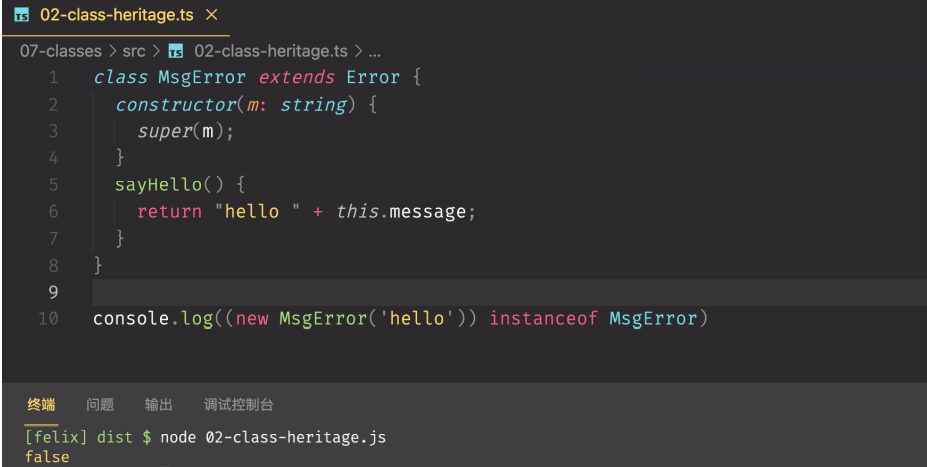

对于一个像下面这样的子类:

class MsgError extends Error {

constructor(m: string) {

super(m);

}

sayHello() {

return "hello " + this.message;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

你可能会发现:

- 方法在构造这些子类所返回的对象上可能是未定义的,所以调用 sayHello 会导致错误

instanceof 将在子类的实例和它们的实例之间被打破,所以

(new MsgError()) instanceof MsgError将返回 false

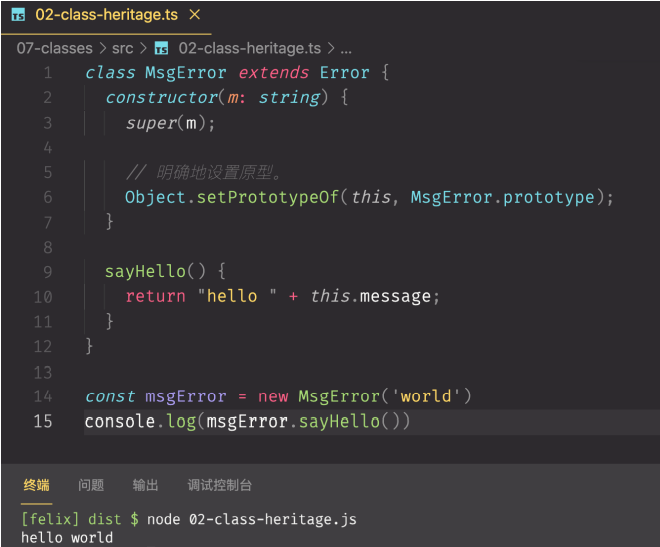

作为建议,你可以在任何 super(...) 调用后立即手动调整原型。

class MsgError extends Error {

constructor(m: string) {

super(m);

// 明确地设置原型。

Object.setPrototypeOf(this, MsgError.prototype);

}

sayHello() {

return "hello " + this.message;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

然而,MsgError 的任何子类也必须手动设置原型。对于不支持 Object.setPrototypeOf 的运行时,你可以使用 proto 来代替。

不幸的是,这些变通方法在 Internet Explorer 10 和更早的版本上不起作用。我们可以手动将原型中的方法复制到实例本身(例如 MsgError.prototype 到 this),但是原型链本身不能被修复。

# 成员的可见性

你可以使用 TypeScript 来控制某些方法或属性对类外的代码是否可见。

# public

类成员的默认可见性是公共(public)的。一个公共(public)成员可以在任何地方被访问。

class Greeter {

public greet() {

console.log("hi!");

}

}

const g = new Greeter();

g.greet();

2

3

4

5

6

7

因为 public 已经是默认的可见性修饰符,所以你永远不需要在类成员上写它,但为了风格 / 可读性的原因,可能会选择这样做。

# protected

受保护的(protected)成员只对它们所声明的类的子类可见。

class Greeter {

public greet() {

console.log("Hello, " + this.getName());

}

protected getName() {

return "hi";

}

}

class SpecialGreeter extends Greeter {

public howdy() {

// 在此可以访问受保护的成员

console.log("Howdy, " + this.getName());

}

}

const g = new SpecialGreeter();

g.greet(); // 没有问题

g.getName(); // 无权访问

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

受保护成员的暴露

派生类需要遵循它们的基类契约,但可以选择公开具有更多能力的基类的子类型。这包括将受保护的成员变成公开。

class Base {

protected m = 10;

}

class Derived extends Base {

// 没有修饰符,所以默认为'公共'('public')

m = 15;

}

const d = new Derived();

console.log(d.m); // OK

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

# private

private 和 protected 一样,但不允许从子类中访问该成员。

class Base {

private x = 0;

}

const b = new Base();

// 不能从类外访问

console.log(b.x);

2

3

4

5

6

class Base {

private x = 0;

}

const b = new Base();

class Derived extends Base {

showX() {

// 不能在子类中访问

console.log(this.x);

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

因为私有(private)成员对派生类是不可见的,所以派生类不能增加其可见性。

跨实例的私有访问

不同的 OOP 语言对同一个类的不同实例,是否可以访问对方的私有成员,有不同的处理方法。虽然像 Java、C#、C++、Swift 和 PHP 等语言允许这样做,但 Ruby 不允许。

TypeScript确实允许跨实例的私有访问:

class A {

private x = 10;

public sameAs(other: A) {

// 可以访问

return other.x === this.x;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

注意事项

像 TypeScript 类型系统的其他方面一样,private 和 protected 只在类型检查中被强制执行。

这意味着 JavaScript 的运行时结构,如 in 或简单的属性查询,仍然可以访问一个私有或保护的成员。

class MySafe {

private secretKey = 12345;

}

// 在 JS 环境中...

const s = new MySafe();

// 将打印 12345

console.log(s.secretKey);

2

3

4

5

6

7

private 也允许在类型检查时使用括号符号进行访问。这使得私有声明的字段可能更容易被单元测试之类的东西所访问,缺点是这些字段是软性私有的,不能严格执行私有特性。

class MySafe {

private secretKey = 12345;

}

const s = new MySafe();

// 在类型检查期间不允许

console.log(s.secretKey);

// 正确

console.log(s["secretKey"]);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

与 TypeScript 的 private 不同,JavaScript 的 private 字段(#)在编译后仍然是 private 的,并且不提供前面提到的像括号符号访问那样的转义窗口,使其成为硬 private。

class Dog {

#barkAmount = 0;

personality = "happy";

constructor() {

// 0

console.log(this.#barkAmount)

}

}

const dog = new Dog()

// undefined

console.log(dog.barkAmount)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

当编译到 ES2021 或更少时,TypeScript 将使用 WeakMaps 来代替 #。

"use strict";

var _Dog_barkAmount;

class Dog {

constructor() {

_Dog_barkAmount.set(this, 0);

this.personality = "happy";

}

}

_Dog_barkAmount = new WeakMap();

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

如果你需要保护你的类中的值免受恶意行为的影响,你应该使用提供硬运行时隐私的机制,如闭包、WeakMaps 或私有字段。请注意,这些在运行时增加的隐私检查可能会影响性能。

# 静态成员

类可以有静态成员。这些成员并不与类的特定实例相关联。它们可以通过类的构造函数对象本身来访问。

class MyClass {

static x = 0;

static printX() {

console.log(MyClass.x);

}

}

console.log(MyClass.x);

MyClass.printX();

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

静态成员也可以使用相同的 public、protected 和 private 可见性修饰符。

class MyClass {

private static x = 0;

}

console.log(MyClass.x);

2

3

4

静态成员也会被继承。

class Base {

static getGreeting() {

return "Hello world";

}

}

class Derived extends Base {

myGreeting = Derived.getGreeting();

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# 特殊静态名称

一般来说,从函数原型覆盖属性是不安全的 / 不可能的。因为类本身就是可以用 new 调用的函数,所以某些静态名称不能使用。像 name、length 和 call 这样的函数属性,定义为静态成员是无效的。

class S {

static name = "S!";

}

2

3

# 为什么没有静态类?

TypeScript(和 JavaScript)没有像 C# 和 Java 那样有一个叫做静态类的结构。

这些结构体的存在,只是因为这些语言强制所有的数据和函数都在一个类里面;因为这个限制在 TypeScript中不存在,所以不需要它们。一个只有一个实例的类,在 JavaScript / TypeScript 中通常只是表示为一个普通的对象。

例如,我们不需要 TypeScript 中的「静态类」语法,因为一个普通的对象(甚至是顶级函数)也可以完成这个工作。

// 不需要 "static" class

class MyStaticClass {

static doSomething() {}

}

// 首选 (备选 1)

function doSomething() {}

// 首选 (备选 2)

const MyHelperObject = {

dosomething() {},

};

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

# 类里的 static 区块

静态块允许你写一串有自己作用域的语句,可以访问包含类中的私有字段。这意味着我们可以用写语句的所有能力来写初始化代码,不泄露变量,并能完全访问我们类的内部结构。

class Foo {

static #count = 0;

get count() {

return Foo.#count;

}

static {

try {

const lastInstances = {

length: 100

};

Foo.#count += lastInstances.length;

}

catch {}

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

# 泛型类

类,和接口一样,可以是泛型的。当一个泛型类用 new 实例化时,其类型参数的推断方式与函数调用的方式相同。

class Box<Type> {

contents: Type;

constructor(value: Type) {

this.contents = value;

}

}

// const b: Box<string>

const b = new Box("hello!");

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

类可以像接口一样使用通用约束和默认值。

静态成员中的类型参数

这段代码是不合法的,可能并不明显,为什么呢?

class Box<Type> {

// 静态成员不能引用类的类型参数。

static defaultValue: Type;

}

// Box<string>.defaultValue = 'hello'

// console.log(Box<number>.defaultValue)

2

3

4

5

6

请记住,类型总是被完全擦除的,在运行时,只有一个 Box.defaultValue 属性。这意味着设置 Box.defaultValue(如果有可能的话)也会改变 Box.defaultValue,这可不是什么好事。一个泛型类的静态成员永远不能引用该类的类型参数。

# 类运行时中的this

重要的是要记住,TypeScript 并没有改变 JavaScript 的运行时行为,而 JavaScript 的运行时行为偶尔很奇特。

比如,JavaScript 对这一点的处理确实是不寻常的:

class MyClass {

name = "MyClass";

getName() {

return this.name;

}

}

const c = new MyClass();

const obj = {

name: "obj",

getName: c.getName,

};

// 输出 "obj", 而不是 "MyClass"

console.log(obj.getName());

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

长话短说,默认情况下,函数内 this 的值取决于函数的调用方式。在这个例子中,因为函数是通过 obj 引用调用的,所以它的 this 值是 obj 而不是类实例。

这很少是你希望发生的事情。TypeScript 提供了一些方法来减轻或防止这种错误。

# 箭头函数

如果你有一个经常会被调用的函数,失去了它的 this 上下文,那么使用一个箭头函数而不是方法定义是有意义的。

class MyClass {

name = "MyClass";

getName = () => {

return this.name;

};

}

const c = new MyClass();

const g = c.getName;

// 输出 "MyClass"

console.log(g());

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

这有一些权衡:

- this 值保证在运行时是正确的,即使是没有经过 TypeScript 检查的代码也是如此

- 这将使用更多的内存,因为每个类实例将有它自己的副本,每个函数都是这样定义的

- 你不能在派生类中使用

super.getName,因为在原型链中没有入口可以获取基类方法

# this 参数

在方法或函数定义中,一个名为 this 的初始参数在 TypeScript 中具有特殊的意义。这些参数在编译过程中会被删除。

// 带有 "this" 参数的 TypeScript 输入

function fn(this: SomeType, x: number) {

/* ... */

}

2

3

4

// 编译后的JavaScript结果

function fn(x) {

/* ... */

}

2

3

4

TypeScript 检查调用带有 this 参数的函数,是否在正确的上下文中进行。我们可以不使用箭头函数,而是在方法定义中添加一个 this 参数,以静态地确保方法被正确调用。

class MyClass {

name = "MyClass";

getName(this: MyClass) {

return this.name;

}

}

const c = new MyClass();

// 正确

c.getName();

// 错误

const g = c.getName;

console.log(g());

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

这种方法做出了与箭头函数方法相反的取舍:

- JavaScript 调用者仍然可能在不知不觉中错误地使用类方法

- 每个类定义只有一个函数被分配,而不是每个类实例一个函数

- 基类方法定义仍然可以通过 super 调用

# this类型

在类中,一个叫做 this 的特殊类型动态地指向当前类的类型。让我们来看看这有什么用:

class Box {

contents: string = "";

// (method) Box.set(value: string): this

set(value: string) {

this.contents = value;

return this;

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

在这里,TypeScript 推断出 set 的返回类型是 this,而不是 Box。现在让我们做一个 Box 的子类:

class ClearableBox extends Box {

clear() {

this.contents = "";

}

}

const a = new ClearableBox();

// const b: ClearableBox

const b = a.set("hello");

console.log(b)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

你也可以在参数类型注释中使用 this:

class Box {

content: string = "";

sameAs(other: this) {

return other.content === this.content;

}

}

const box = new Box()

console.log(box.sameAs(box))

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

这与其他写法不同:Box,如果你有一个派生类,它的 sameAs 方法现在只接受该同一派生类的其他实例。

class Box {

content: string = "";

sameAs(other: this) {

return other.content === this.content;

}

}

class DerivedBox extends Box {

otherContent: string = "?";

}

const base = new Box();

const derived = new DerivedBox();

derived.sameAs(base);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# 基于类型守卫的 this

你可以在类和接口的方法的返回位置使用 this is Type。当与类型缩小混合时(例如 if 语句),目标对象的类型将被缩小到指定的 Type。

class FileSystemObject {

isFile(): this is FileRep {

return this instanceof FileRep;

}

isDirectory(): this is Directory {

return this instanceof Directory;

}

isNetworked(): this is Networked & this {

return this.networked;

}

constructor(public path: string, private networked: boolean) {

}

}

class FileRep extends FileSystemObject {

constructor(path: string, public content: string) {

super(path, false);

}

}

class Directory extends FileSystemObject {

children: FileSystemObject[];

}

interface Networked {

host: string;

}

const fso: FileSystemObject = new FileRep("foo/bar.txt", "foo");

if (fso.isFile()) {

// const fso: FileRep

fso.content;

} else if (fso.isDirectory()) {

// const fso: Directory

fso.children;

} else if (fso.isNetworked()) {

// const fso: Networked & FileSystemObject

fso.host;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

基于 this 的类型保护的一个常见用例,是允许对一个特定字段进行懒惰验证。例如,这种情况下,当 hasValue 被验证为真时,就会从框内持有的值中删除一个未定义值。

class Box <T> {

value?: T;

hasValue(): this is { value: T} {

return this.value !== undefined;

}

}

const box = new Box();

box.value = "Gameboy";

// (property) Box<unknown>.value?: unknownbox.value;

if (box.hasValue()) {

// (property) value: unknown

box.value;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

# 参数属性

TypeScript提供了特殊的语法,可以将构造函数参数变成具有相同名称和值的类属性。这些被称为参数 属性,通过在构造函数参数前加上可见性修饰符 public、private、protected 或 readonly 中的一个来创建。由此产生的字段会得到这些修饰符。

class Params {

constructor(public readonly x: number, protected y: number, private z: number)

{

// No body necessary

}

}

const a = new Params(1, 2, 3);

// (property) Params.x: number

console.log(a.x);

console.log(a.z);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

# 类表达式

类表达式与类声明非常相似。唯一真正的区别是,类表达式不需要一个名字,尽管我们可以通过它们最终绑定的任何标识符来引用它们。

const someClass = class<Type> {

content: Type;

constructor(value: Type) {

this.content = value;

}

};

// const m: someClass<string>

const m = new someClass("Hello, world");

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# 抽象类和成员

TypeScript中的类、方法和字段可以是抽象的。

一个抽象的方法或抽象的字段是一个没有提供实现的方法或字段。这些成员必须存在于一个抽象类中,不能直接实例化。

抽象类的作用是作为子类的基类,实现所有的抽象成员。当一个类没有任何抽象成员时,我们就说它是具体的。

让我们看一个例子:

abstract class Base {

abstract getName(): string;

printName() {

console.log("Hello, " + this.getName());

}

}

const b = new Base();

2

3

4

5

6

7

我们不能用 new 来实例化 Base,因为它是抽象的。相反,我们需要创建一个派生类并实现抽象成员。

class Derived extends Base {

getName() {

return "world";

}

}

const d = new Derived();

d.printName();

2

3

4

5

6

7

# 抽象构造签名

有时你想接受一些类的构造函数,产生一个从某些抽象类派生出来的类的实例。

例如,你可能想写这样的代码:

function greet(ctor: typeof Base) {

const instance = new ctor();

instance.printName();

}

2

3

4

TypeScript 正确地告诉你,你正试图实例化一个抽象类。毕竟,鉴于 greet 的定义,写这段代码是完全合法的,它最终会构造一个抽象类。

// 槽糕

greet(Base);

2

相反,你想写一个函数,接受具有结构化签名的东西:

function greet(ctor: new() => Base) {

const instance = new ctor();

instance.printName();

}

greet(Derived);

greet(Base);

2

3

4

5

6

现在 TypeScript 正确地告诉你哪些类的构造函数可以被调用:Derived 可以,因为它是具体的,但 Base 不能。

# 类之间的关系

在大多数情况下,TypeScript 中的类在结构上与其他类型相同,是可以比较的。

例如,这两个类可以互相替代使用,因为它们是相同的:

class Point1 {

x = 0;

y = 0;

}

class Point2 {

x = 0;

y = 0;

}

// 正确

const p: Point1 = new Point2();

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

同样地,即使没有明确的继承,类之间的子类型关系也是存在的:

class Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

class Employee {

name: string;

age: number;

salary: number;

}

// 正确

const p: Person = new Employee();

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

这听起来很简单,但有几种情况似乎比其他情况更奇怪。

空的类没有成员。在一个结构化类型系统中,一个没有成员的类型通常是其他任何东西的超类型。所以 如果你写了一个空类(不要),任何东西都可以用来代替它。

class Empty {

}

function fn(x: Empty) {

// 不能用 'x' 做任何事

}

// 以下调用均可

!fn(window);

fn({});

fn(fn);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9