TypeScript Office - 对象类型

TypeScript Office - 对象类型

# 对象类型

在 JavaScript 中,我们分组和传递数据的基本方式是通过对象。在 TypeScript 中,我们通过对象类型来表示这些对象。

正如我们所见,它们可以是匿名的:

function greet(person: { name: string; age: number }) {

return "Hello " + person.name;

}

2

3

或者可以通过使用一个接口来命名它们:

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

function greet(person: Person) {

return "Hello " + person.name;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

或一个类型别名:

type Person = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

function greet(person: Person) {

return "Hello " + person.name;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

在上面的三个例子中,我们写了一些函数,这些函数接收包含属性 name(必须是一个 string )和 age (必须是一个 number )的对象。

# 属性修改器

对象类型中的每个属性都可以指定几件事:类型、属性是否是可选的,以及属性是否可以被写入。

# 可选属性

很多时候,我们会发现自己处理的对象可能有一个属性设置。在这些情况下,我们可以在这些属性的名字后面加上一个问号(?),把它们标记为可选的。

type Shape = {}

interface PaintOptions {

shape: Shape;

xPos?: number;

yPos?: number;

}

function paintShape(opts: PaintOptions) {

// ...

}

const shape:Shape = {}

paintShape({ shape });

paintShape({ shape, xPos: 100 });

paintShape({ shape, yPos: 100 });

paintShape({ shape, xPos: 100, yPos: 100 });

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

在这个例子中,xPos 和 yPos 都被认为是可选的。我们可以选择提供它们中的任何一个,所以上面对 paintShape 的每个调用都是有效的。所有的可选性实际上是说,如果属性被设置,它最好有一个特定的类型。

我们也可以从这些属性中读取,但当我们在 strictNullChecks 下读取时,TypeScript 会告诉我们它们可能是未定义的。

function paintShape(opts: PaintOptions) {

let xPos = opts.xPos;

let yPos = opts.yPos;

// ...

}

2

3

4

5

在 JavaScript 中,即使该属性从未被设置过,我们仍然可以访问它,它只是会给我们未定义的值。我们可以专门处理未定义。

function paintShape(opts: PaintOptions) {

let xPos = opts.xPos === undefined ? 0 : opts.xPos;

let yPos = opts.yPos === undefined ? 0 : opts.yPos;

// ...

}

2

3

4

5

请注意,这种为未指定的值设置默认值的模式非常普遍,以至于 JavaScript 有语法来支持它。

function paintShape({ shape, xPos = 0, yPos = 0 }: PaintOptions) {

console.log("x coordinate at", xPos);

console.log("y coordinate at", yPos);

// ...

}

2

3

4

5

在这里,我们为 paintShape 的参数使用了一个解构模式,并为 xPos 和 yPos 提供了默认值。现在 xPos 和 yPos 都肯定存在于 paintShape 的主体中,但对于 paintShape 的任何调用者来说是可选的。

请注意,目前还没有办法将类型注释放在解构模式中。这是因为下面的语法在 JavaScript 中已经有了不同的含义。

function draw({ shape: Shape, xPos: number = 100 /*...*/ }) {

render(shape);

render(xPos);

}

2

3

4

在一个对象解构模式中,shape: Shape 意味着获取属性 shape,并在本地重新定义为一个名为 Shape 的变量。同样,xPos: number 创建一个名为 number 的变量,其值基于参数的 xPos。

# 只读属性

对于 TypeScript,属性也可以被标记为只读。虽然它不会在运行时改变任何行为,但在类型检查期间,一个标记为只读的属性不能被写入。

interface SomeType {

readonly prop: string;

}

function doSomething(obj: SomeType) {

// 可以读取 'obj.prop'.

console.log(`prop has the value '${obj.prop}'.`);

// 但不能重新设置值

obj.prop = "hello";

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

使用 readonly 修饰符并不一定意味着一个值是完全不可改变的。或者换句话说,它的内部内容不能被改变,它只是意味着该属性本身不能被重新写入。

interface Home {

readonly resident: { name: string; age: number };

}

function visitForBirthday(home: Home) {

// 我们可以从'home.resident'读取和更新属性。

console.log(`Happy birthday ${home.resident.name}!`);

home.resident.age++;

}

function evict(home: Home) {

// 但是我们不能写到'home'上的'resident'属性本身。

home.resident = {

name: "Victor the Evictor",

age: 42,

};

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

管理对 readonly 含义的预期是很重要的。在 TypeScript 的开发过程中,对于一个对象应该如何被使用的问题,它是有用的信号。TypeScript 在检查两个类型的属性是否兼容时,并不考虑这些类型的属性是否是 readonly,所以 readony 属性也可以通过别名来改变。

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

interface ReadonlyPerson {

readonly name: string;

readonly age: number;

}

let writablePerson: Person = {

name: "Person McPersonface",

age: 42,

};

// 正常工作

let readonlyPerson: ReadonlyPerson = writablePerson;

console.log(readonlyPerson.age); // 打印 '42'

writablePerson.age++;

console.log(readonlyPerson.age); // 打印 '43'

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# 索引签名

有时你并不提前知道一个类型的所有属性名称,但你知道值的形状。

在这些情况下,你可以使用一个索引签名来描述可能的值的类型,比如说:

interface StringArray {

[index: number]: string;

}

const myArray: StringArray = ['a', 'b'];

const secondItem = myArray[1];

2

3

4

5

上面,我们有一个 StringArray 接口,它有一个索引签名。这个索引签名指出,当一个 StringArray 被数字索引时,它将返回一个字符串。

索引签名的属性类型必须是 string 或 number 。

支持两种类型的索引器是可能的,但是从数字索引器返回的类型必须是字符串索引器返回的类型的子类型。这是因为当用「数字」进行索引时,JavaScript 实际上会在索引到一个对象之前将其转换为「字符串」。这意味着用 100(一个数字)进行索引和用 "100"(一个字符串)进行索引是一样的,所以两者需要一致。

interface Animal {

name: string;

}

interface Dog extends Animal {

breed: string;

}

interface NotOkay {

[x: number]: Animal;

[x: string]: Dog;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

虽然字符串索引签名是描述「字典」模式的一种强大方式,但它也强制要求所有的属性与它们的返回类型相匹配。这是因为字符串索引声明 obj.property 也可以作为 obj["property"]。在下面的例子中,name 的类型与字符串索引的类型不匹配,类型检查器会给出一个错误:

interface NumberDictionary {

[index: string]: number;

length: number; // ok

name: string;

}

2

3

4

5

然而,如果索引签名是属性类型的联合,不同类型的属性是可以接受的:

interface NumberOrStringDictionary {

[index: string]: number | string;

length: number; // 正确, length 是 number 类型

name: string; // 正确, name 是 string 类型

}

2

3

4

5

最后,你可以使索引签名为只读,以防止对其索引的赋值:

interface ReadonlyStringArray {

readonly [index: number]: string;

}

let myArray: ReadonlyStringArray = getReadOnlyStringArray();

myArray[2] = "Mallory";

2

3

4

5

你不能设置 myArray[2],因为这个索引签名是只读的。

# 扩展类型

有一些类型可能是其他类型的更具体的版本,这是很常见的。例如,我们可能有一个 BasicAddress 类型,描述发送信件和包裹所需的字段。

interface BasicAddress {

name?: string;

street: string;

city: string;

country: string;

postalCode: string;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

在某些情况下,这就足够了,但是如果一个地址的小区内有多个单元,那么地址往往有一个单元号与之相关。我们就可以描述一个 AddressWithUnit:

interface AddressWithUnit {

name?: string;

unit: string;

street: string;

city: string;

country: string;

postalCode: string;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

这就完成了工作,但这里的缺点是,当我们的变化是纯粹的加法时,我们不得不重复 BasicAddress 的所有其他字段。相反,我们可以扩展原始的 BasicAddress 类型,只需添加 AddressWithUnit 特有的新字段:

interface BasicAddress {

name?: string;

street: string;

city: string;

country: string;

postalCode: string;

}

interface AddressWithUnit extends BasicAddress {

unit: string;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

接口上的 extends 关键字,允许我们有效地从其他命名的类型中复制成员,并添加我们想要的任何新成员。这对于减少我们不得不写的类型声明模板,以及表明同一属性的几个不同声明可能是相关的意图来说,是非常有用的。例如,AddressWithUnit 不需要重复 street 属性,而且因为 street 源于 BasicAddress ,我们会知道这两种类型在某种程度上是相关的。

接口也可以从多个类型中扩展。

interface Colorful {

color: string;

}

interface Circle {

radius: number;

}

interface ColorfulCircle extends Colorful, Circle {}

const cc: ColorfulCircle = {

color: "red",

radius: 42,

};

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# 交叉类型

接口允许我们通过扩展其他类型建立起新的类型。TypeScript 提供了另一种结构,称为交叉类型,主要用于组合现有的对象类型。

交叉类型是用 & 操作符定义的。

interface Colorful {

color: string;

}

interface Circle {

radius: number;

}

type ColorfulCircle = Colorful & Circle;

const cc: ColorfulCircle = {

color: "red",

radius: 42,

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

在这里,我们将 Colorful 和 Circle 相交,产生了一个新的类型,它拥有 Colorful 和 Circle 的所有成员。

function draw(circle: Colorful & Circle) {

console.log(`Color was ${circle.color}`);

console.log(`Radius was ${circle.radius}`);

}

// 正确

draw({ color: "blue", radius: 42 });

// 错误

draw({ color: "red", raidus: 42 });

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

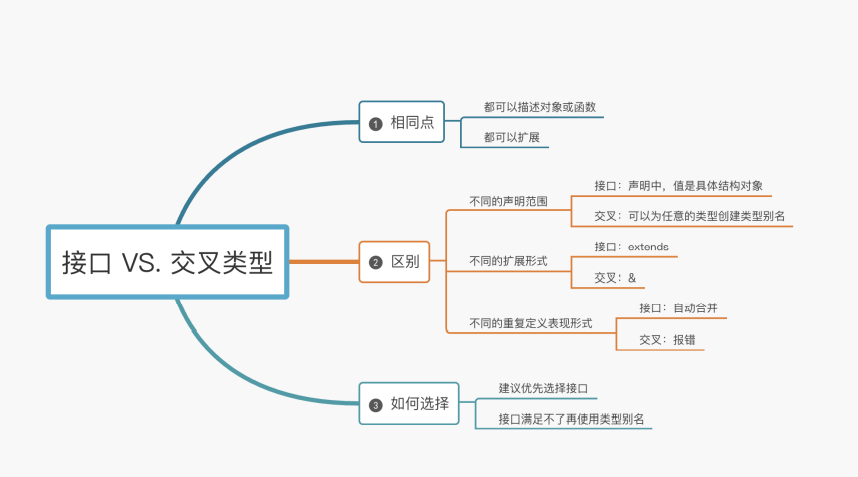

# 接口与交叉类型

我们刚刚看了两种组合类型的方法,它们很相似,但实际上有细微的不同。对于接口,我们可以使用 extends 子句来扩展其他类型,而对于交叉类型,我们也可以做类似的事情,并用类型别名来命名结果。两者之间的主要区别在于如何处理冲突,这种区别通常是你在接口和交叉类型的类型别名之间选择一个的主要原因之一。

接口可以定义多次,多次的声明会自动合并:

interface Sister {

name: string;

}

interface Sister {

age: number;

}

const sisterAn: Sister = {

name: 'sisterAn'

}

const sisterRan: Sister = {

name: 'sisterRan',

age: 12

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

但是类型别名如果定义多次,会报错:

type Sister = {

name: string;

}

type Sister = {

age: number;

}

2

3

4

5

6

# 泛型对象类型

让我们想象一下,一个可以包含任何数值的盒子类型:字符串、数字、长颈鹿等等。

interface Box {

contents: any;

}

2

3

现在,内容属性的类型是任意,这很有效,但会导致下一步的意外。

我们可以使用 unknown,但这意味着在我们已经知道内容类型的情况下,我们需要做预防性检查,或者使用容易出错的类型断言。

interface Box {

contents: unknown;

}

let x: Box = {

contents: "hello world",

};

// 我们需要检查 'x.contents'

if (typeof x.contents === "string") {

console.log(x.contents.toLowerCase());

}

// 或者用类型断言

console.log((x.contents as string).toLowerCase());

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

一种安全的方法是为每一种类型的内容搭建不同的盒子类型:

interface NumberBox {

contents: number;

}

interface StringBox {

contents: string;

}

interface BooleanBox {

contents: boolean;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

但这意味着我们必须创建不同的函数,或函数的重载,以对这些类型进行操作:

function setContents(box: StringBox, newContents: string): void;

function setContents(box: NumberBox, newContents: number): void;

function setContents(box: BooleanBox, newContents: boolean): void;

function setContents(box: { contents: any }, newContents: any) {

box.contents = newContents;

}

2

3

4

5

6

那是一个很大的模板。此外,我们以后可能需要引入新的类型和重载。这是令人沮丧的,因为我们的盒子类型和重载实际上都是一样的。

相反,我们可以做一个通用的 Box 类型,声明一个类型参数:

interface Box<Type> {

contents: Type;

}

2

3

你可以把这句话理解为:一个类型的盒子,是它的内容具有类型的东西。以后,当我们引用 Box 时,我们必须给一个类型参数来代替 Type。

let box: Box<string>;

把 Box 想象成一个真实类型的模板,其中 Type 是一个占位符,会被替换成其他类型。当 TypeScript 看到 Box<string> 时,它将用字符串替换 Box<Type> 中的每个 Type 实例,并最终以 { contents: string } 这样的方式工作。换句话说,Box<string> 和我们之前的 StringBox 工作起来是一样的。

interface Box<Type> {

contents: Type;

}

interface StringBox {

contents: string;

}

let boxA: Box<string> = { contents: "hello" };

boxA.contents;

let boxB: StringBox = { contents: "world" };

boxB.contents;

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

盒子是可重用的,因为 Type 可以用任何东西来代替。这意味着当我们需要一个新类型的盒子时,我们根本不需要声明一个新的盒子类型(尽管如果我们想的话,我们当然可以)。

interface Box<Type> {

contents: Type;

}

interface Apple {

// ....

}

// 等价于 '{ contents: Apple }'.

type AppleBox = Box<Apple>;

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

这也意味着我们可以完全避免重载,而是使用通用函数。

function setContents<Type>(box: Box<Type>, newContents: Type) {

box.contents = newContents;

}

2

3

值得注意的是,类型别名也可以是通用的。我们可以定义我们新的 Box<Type> 接口:

interface Box<Type> {

contents: Type;

}

2

3

通过使用一个类型别名来代替:

type Box<Type> = {

contents: Type;

}

2

3

由于类型别名与接口不同,它不仅可以描述对象类型,我们还可以用它来编写其他类型的通用辅助类型。

type OrNull<Type> = Type | null;

type OneOrMany<Type> = Type | Type[];

type OneOrManyOrNull<Type> = OrNull<OneOrMany<Type>>;

type OneOrManyOrNullStrings = OneOrManyOrNull<string>;

2

3

4

我们将在稍后回到类型别名。

通用对象类型通常是某种容器类型,它的工作与它们所包含的元素类型无关。数据结构以这种方式工作是很理想的,这样它们就可以在不同的数据类型中重复使用。

# 数组类型

我们一直在使用这样一种类型:数组类型。每当我们写出 number[] 或 string[] 这样的类型时,这实际上只是 Array 和 Array 的缩写。

function doSomething(value: Array<string>) {

// ...

}

let myArray: string[] = ["hello", "world"];

// 这两样都能用

doSomething(myArray);

doSomething(new Array("hello", "world"));

2

3

4

5

6

7

和上面的 Box 类型一样,Array 本身也是一个通用类型。

interface Array<Type> {

/**

* 获取或设置数组的长度。

*/

length: number;

/**

* 移除数组中的最后一个元素并返回。

*/

pop(): Type | undefined;

/**

* 向一个数组添加新元素,并返回数组的新长度。

*/

push(...items: Type[]): number;

// ...

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

现代 JavaScript 还提供了其他通用的数据结构,比如 Map,Set 和 Promise。这实际上意味着,由于 Map、Set 和 Promise 的行为方式,它们可以与任何类型的集合一起工作。

# 只读数组类型

ReadonlyArray 是一个特殊的类型,描述了不应该被改变的数组。

function doStuff(values: ReadonlyArray<string>) {

// 我们可以从 'values' 读数据...

const copy = values.slice();

console.log(`第一个值是 ${values[0]}`);

// ...但我们不能改变 'vulues' 的值。

values.push("hello!"); // 报错:类型 「readonly string" 上不存在属性 "push"

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

和属性的 readonly 修饰符一样,它主要是一个我们可以用来了解意图的工具。当我们看到一个返回 ReadonlyArrays 的函数时,它告诉我们我们根本不打算改变其内容,而当我们看到一个消耗 ReadonlyArrays 的函数时,它告诉我们可以将任何数组传入该函数,而不用担心它会改变其内容。

与 Array 不同,没有一个我们可以使用的 ReadonlyArray 构造函数。

// 报错:"ReadonlyArray" 仅表示类型,但在此处却作为值使用。

new ReadonlyArray("red", "green", "blue");

2

相反,我们可以将普通的 Array 分配给 ReadonlyArray。

const roArray: ReadonlyArray<string> = ["red", "green", "blue"];

正如 TypeScript为 Array<Type> 提供了 Type[] 的速记语法一样,它也为 ReadonlyArray<Type> 提供了只读 Type[] 的速记语法。

function doStuff(values: readonly string[]) {

// 我们可以从 'values' 读数据...

const copy = values.slice();

console.log(`The first value is ${values[0]}`);

// 但我们不能改变 'vulues' 的值。

values.push("hello!"); // 报错:类型 「readonly string[]" 上不存在属性 "push"

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

最后要注意的是,与 readony 属性修改器不同,可分配性在普通 Array 和 ReadonlyArray 之间不是双向的。

let x: readonly string[] = [];

let y: string[] = [];

x = y;

y = x; // 报错:类型 "readonly string[]" 为 "readonly",不能分配给可变类型"string[]".

2

3

4

# 元组类型

Tuple 类型是另一种 Array 类型,它确切地知道包含多少个元素,以及它在特定位置包含哪些类型。

type StringNumberPair = [string, number];

这里,StringNumberPair 是一个 string 和 number 的元组类型。像 ReadonlyArray 一样,它在运行时没有表示,但对 TypeScript 来说是重要的。对于类型系统来说,StringNumberPair 描述了其索引 0 包含字符串和索引 1 包含数字的数组。

function doSomething(pair: [string, number]) {

const a = pair[0];

const b = pair[1];

// ...

}

doSomething(["hello", 42])

2

3

4

5

6

如果我们试图索引超过元素的数量,我们会得到一个错误:

function doSomething(pair: [string, number]) {

const c = pair[2];

}

2

3

我们还可以使用 JavaScript 的数组析构来对元组进行解构。

function doSomething(stringHash: [string, number]) {

const [inputString, hash] = stringHash;

console.log(inputString);

console.log(hash);

}

2

3

4

5

除了这些长度检查,像这样的简单元组类型等同于 Array 的版本,它为特定的索引声明属性,并且用数字字面类型声明长度。

interface StringNumberPair {

// 专有属性

length: 2;

0: string;

1: number;

// 其他 'Array<string | number>' 成员...

slice(start?: number, end?: number): Array<string | number>;

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

另一件你可能感兴趣的事情是,元组可以通过在元素的类型后面写出问号(?):可选的元组,元素只能出现在末尾,而且还影响到长度的类型。

type Either2dOr3d = [number, number, number?];

function setCoordinate(coord: Either2dOr3d) {

const [x, y, z] = coord;

console.log(`提供的坐标有 ${coord.length} 个维度`);

}

2

3

4

5

图元也可以有其余元素,这些元素必须是 array / tuple 类型。

type StringNumberBooleans = [string, number, ...boolean[]];

type StringBooleansNumber = [string, ...boolean[], number];

type BooleansStringNumber = [...boolean[], string, number];

2

3

- StringNumberBooleans 描述了一个元组,其前两个元素分别是字符串和数字,但后面可以有任意数量的布尔

- StringBooleansNumber 描述了一个元组,其第一个元素是字符串,然后是任意数量的布尔运算,最后是一个数字

- BooleansStringNumber 描述了一个元组,其起始元素是任意数量的布尔运算,最后是一个字符串,然后是一个数字

一个有其余元素的元组没有集合的「长度」:它只有一组不同位置的知名元素。

const a: StringNumberBooleans = ["hello", 1];

const b: StringNumberBooleans = ["beautiful", 2, true];

const c: StringNumberBooleans = ["world", 3, true, false, true, false, true];

2

3

为什么可选元素和其余元素可能是有用的?它允许 TypeScript 将 tuples 与参数列表相对应。

function readButtonInput(...args: [string, number, ...boolean[]]) {

const [name, version, ...input] = args;

// ...

}

2

3

4

基本上等同于:

function readButtonInput(name: string, version: number, ...input: boolean[]) {

// ...

}

2

3

当你想用一个其余(rest)参数接受可变数量的参数,并且你需要一个最小的元素数量,但你不想引入中间变量时,这很方便。

# 只读元组类型

关于 tuple 类型的最后一点说明:tuple 类型有只读特性,可以通过在它们前面粘贴一个 readonly 修饰符来指定——就像数组的速记语法一样。

function doSomething(pair: readonly [string, number]) {

// ...

}

2

3

正如你所期望的,在 TypeScript 中不允许向只读元组的任何属性写入。

function doSomething(pair: readonly [string, number]) {

pair[0] = "hello!";

}

2

3

在大多数代码中,元组往往被创建并不被修改,所以在可能的情况下,将类型注释为只读元组是一个很好的默认。这一点也很重要,因为带有 const 断言的数组字面量将被推断为只读元组类型。

let point = [3, 4] as const;

function distanceFromOrigin([x, y]: [number, number]) {

return Math.sqrt(x ** 2 + y ** 2);

}

distanceFromOrigin(point);

2

3

4

5

在这里,distanceFromOrigin 从未修改过它的元素,而是期望一个可变的元组。由于 point 的类型被推断为只读的 [3, 4],它与 [number, number] 不兼容,因为该类型不能保证 point 的元素不被修改。